Property Releases - Not Necessary One Court Rules

For years, it has been espoused that, in order for you to use someone else's property in a commercial way, you needed permission from the owner of that property in the form of a Property Release, much like a Model Release. No so, says the U.S. District Court in Northern California, in a rare case that likely will have far reaching consequences.

For years, it has been espoused that, in order for you to use someone else's property in a commercial way, you needed permission from the owner of that property in the form of a Property Release, much like a Model Release. No so, says the U.S. District Court in Northern California, in a rare case that likely will have far reaching consequences.

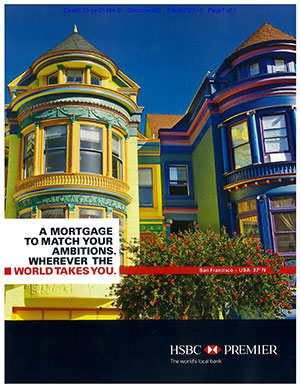

In the case of Robinson v. HSBC USA, Mr. Robinson's home, an often-photographed Victorian-era home in San Francisco, was used in advertising for the HSBC bank. (Read the decision here). The case, interestingly enough, was brought against the bank, one can assume, because they had the deep pockets for an award, as opposed to being brought against the photographer, who had far shallower pockets than a multi-national bank.

The front of the brochure, is at right, where Robinson's home is the yellow one.

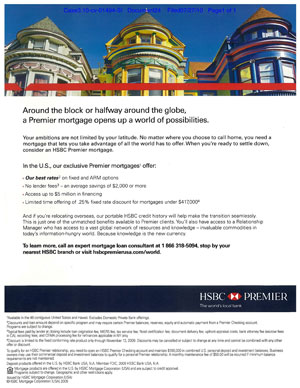

With the court's decision, it was dismissed "with prejudice", which barrs Robinson from bringing another case on the same claim. At right is the inside of the brochure - a second use of Robinson's home.

With the court's decision, it was dismissed "with prejudice", which barrs Robinson from bringing another case on the same claim. At right is the inside of the brochure - a second use of Robinson's home.Over at the Property, Intangible blog, there is an excellent dissection of the case by an intellectual property lawyer that's well worth the read. Carolyn Wright, over at A Photo Attorney, discusses that there is almost no need for property releases in the United States, and she writes a bit about it here.

Essentially, there was no libel or defamation, nor even the suggestion that Robinson had a home loan with HSBC. Further, there was no trademark issue (like a logo visible in the image), nor a copyright issue. Further, the image was taken without trespassing on private property.

While I'm not a lawyer, and further, this isn't legal advice, it seems that unless you're going to use an image of someone's home and say "hey, here's a great place to open a brothel", or "this house looks like a crack house", a property release isn't as necessary as we have all been led to believe in the past.

Please post your comments by clicking the link below. If you've got questions, please pose them in our Photo Business Forum Flickr Group Discussion Threads.

4 comments:

Well, this just serves to illustrate the whole irritating muddle around model releases as well. It really all depends what you mean by "need".

The law may differ in the US, but in Australia, you don't need a model release to publish a picture of someone (or something), unless, as you've pointed out, you defame or libel them, or imply endorsement of your product when none exists.

None of these have to do with the taking or publication of the photograph, merely the context in which it is used.

But here's the rub - and what I mean about the definition of "need": if the photograph is for use by a client or stock library who requires property or model releases for your image to be eligible for use, then yes, you need one.

It seems to me, the point has always been that if you're unsure about how you might want to use an image commercially in the future, then it's always best to cover yourself with a release.

Of course the interesting point of your post is that we may now consider making some of our non-property released images, which we had considered not commercially usable, available for publication.

I would have thought the case was brought against the bank, not because it has deeper pockets than the photographer, but because it the bank using the image! It is not a photographer's responsibility to get a release in order to be able to licence an image to someone, instead they get the release because their client needs permission to use the image from both the photographer and the model/property owner. Most times the client won't licence an image from a photographer unless the photographer can say "yes, you have all the rights you need to use this image", but it is still the clients responsibility to ensure that they clear the rights.

I have to say that I'm slightly puzzled by this ruling. Admittedly the situation is different from the use of a person's image where an implied endorsement exists, but just wait until someone, spurred on by this judgement, tries to use an image of the Eiffel Tower without a property release - that would certainly be an interesting test of French copyright law! (For those of you who do not know what I'm referring to, the owners of the Eiffel Tower claim copyright of all images made of the tower since the new lights were installed).

Simon:

The US, through its judiciary, will happily review alleged infringements the copyright in the lighting pattern of the Eiffel Tower as it would any other claimed artwork. It may or may not enforce any such alleged right, but it will take the claim perfectly seriously because it's a copyright and we have a copyright treaty in place that requires us to extend comity to French copyrights within certain limits.

However, there is no copyright in the house. They might have claimed copyright in the paint scheme or something, but that doesn't usually fly. Plaintiffs didn't even allege copyright infringement in their case, which is Federal only in diversity and claims no Federal legal basis. So your comparison, other than that this decision might lead people to make incorrect conclusions about copyright versus right of publicity which is an old and established problem anyway, is just not relevant.

This is pure ROP (right of publicity and/or right of privacy) law, with some other quite frankly desperate theories (Unfair competition? Oh, please.) thrown in in hope that something sticks. And the District Court quite rightly reached the conclusion that nothing in the common law or any CA statute advances real property a ROP. Nor, to the best of my knowledge, does the common or statute law of any other US state. Which, IMO, is a very good thing. It's one thing to extend a person ROP in their likeness. It's quite another to say that you have to worry about taking a picture of an interesting building automatically means you can't use the picture for anything because the building was interesting!

M

Of course there’s no property release debate when it comes to using a public building photo in an editorial context, but even in a commercial circumstance I’ve always felt the property release rulings the past decade or so were contrary to the spirit of the First Amendment. It’s almost like real estate sales people were saying to a prospective buyer, “And don’t forget there’s another asset available to you when you buy this property… it’s the revenue received from a law suit when some photographer comes along and photographs your building and sells the resulting picture for commercial gain.”

Post a Comment